| Project Home | About the Scans | Browse Gallery | Image Map | Support Data | Resources | Ephemeris |

Featured Image - 02/19/2008

Apennine Bench Formation: Unique Lunar Volcanism

The Apennine Bench Formation is a mysterious smooth plains unit whose origin has beguiled lunar scientists since the Apollo days. What's the mystery? These plains look very similar to common mare basalts, yet they are not as dark or as smooth. Mare basalts are dark because they contain a lot of iron and, often, titanium. Lunar scientists generally agree that Apennine Bench materials are lighter because they do not contain as much iron or titanium.

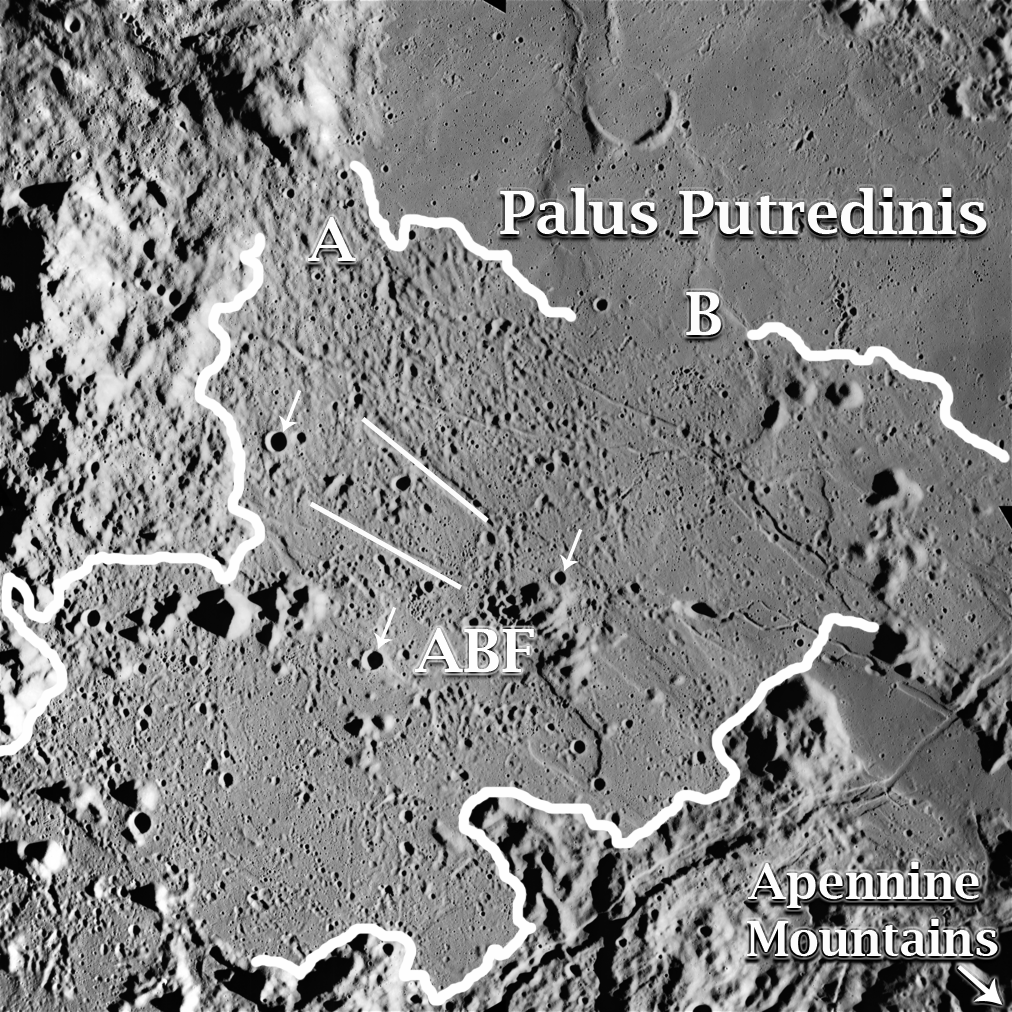

Why is the Apennine Bench not as smooth as other basalts? The Apennine Bench was probably once as smooth as typical mare basalts, but these once smooth plains were heavily modified by later impact ejecta, secondary craters, tectonic forces, and mare volcanism. The Apennine Bench Formation is located to the southeast of Archimedes Crater (see Figure 2 below), and is covered with ejecta (labeled A in Figure 1 below) and secondary craters (small arrows in Figure 1 below) from the impact that formed Archimedes Crater, causing the once smooth plains to become pockmarked and rough. The Apennine Bench is also fractured and cut by graben (white lines in Figure 1 below) that are generally radial to the Imbrium basin. Palus Putredinis to the north is composed of darker mare basalts and may partially cover part of the Apennine Bench Formation at B in Figure 1 below. The older the basalt, the more likely it is to be modified by later events such as impacts, tectonic faulting, or subsequent volcanism.

So if the Apennine Bench is not mare volcanism, what is it? Based on chemical data from Apollo samples and remote sensing, the Apennine Bench is probably non-mare volcanism that erupted after the Imbrium basin formed but before the nearby mare basalt flows in Palus Putredinis. The Apennine Bench volcanism is different in that it contains less iron and titanium than later mare volcanism, but it also contains a unique chemical component known as KREEP, which is enriched in potassium (K), rare-earth elements (REEs), and phosphorous (P). The KREEP elements are generally incompatible with most mineral structures and do not concentrate in typical volcanic materials, which makes the KREEP-enriched volcanic rocks of the Apennine Bench Formation unique. Because the origins of both the KREEP component and the Apennine Bench Formation materials are still mysterious, the bench is an important target for field investigation by future human lunar explorers. Nevertheless, it is clear that volcanism on the Moon is complex and has erupted from a variety of different magma sources: some like the mare basalts are enriched in iron and titanium, while others are not, and some like the Apennine Bench are enriched in KREEP.Figure 1. AS15-M-0418: Apennine Bench Formation

The approximate boundaries of the Apennine Bench Formation (ABF) are outlined in white. The once smooth light-colored plains of the Apennine Bench Formation are pockmarked by secondary craters (small white arrows) and blanketing ejecta from Archimedes Crater (A). Graben formed from tectonic stresses in Imbrium basin (white lines) tear across the plains, and later mare lava flows (B) subdue portions of the landscape.

(Apollo Image AS15-M-0418 [NASA/JSC/Arizona State University])

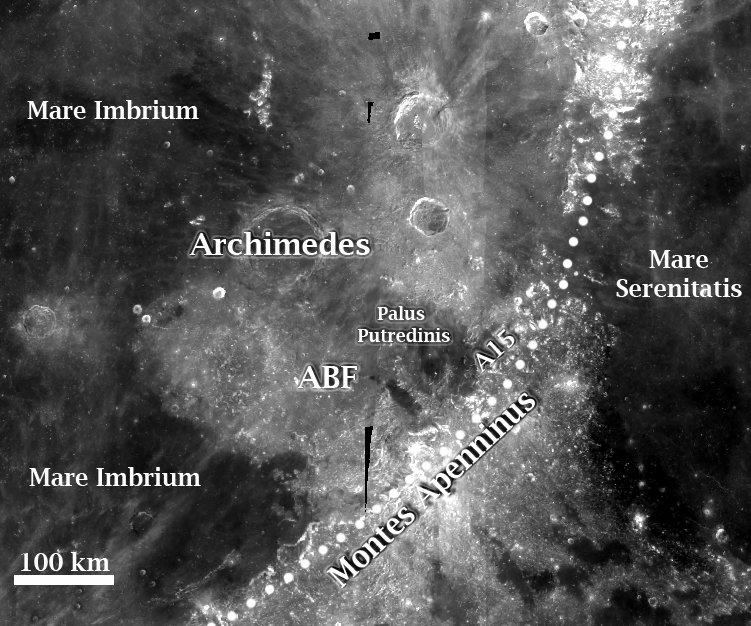

Figure 2. Overview of the Apennine Bench Formation (ABF) in relation to the Apollo 15 landing site and Archimedes Crater (Clementine UV/VIS 750nm image mosaic).

The Apennine Bench Formation (ABF) is located within the second ring of Imbrium (dotted line). Apollo 15 (A15) landed to the northeast. Debris from Archimedes Crater to the northwest has heavily modified the once smooth plains of the Apennine Bench Formation. The Apennine Mountains (or Montes Apenninus) are named for the Apennine Mountains in Italy that form a 1000-km long mountain range that forms the backbone of the country.

References: P. D. Spudis, 1978, Composition and Origin of the Apennine Bench Formation, Proceedings of the 9th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, p. 3379-3394.

Tweet

|

|

Space Exploration Resources |

|

LPI LPI

|